Coronavirus: How does the global market chaos compare with the 2008 crash?

The extent of this week's falls on the back of coronavirus fears has shocked even experienced traders and investors.

Friday 28 February 2020 21:07, UK

The title of the note sent to clients today by the European Economics team at Bank of America Securities summed up how market participants feel at the end of a gruelling week: 'Make this stop'.

Big falls in equity markets of between 10-15% are not unusual. For example, the FTSE-100 fell by 12% between early October and late December 2018, while the index suffered a similar rout across two weeks in August 2015.

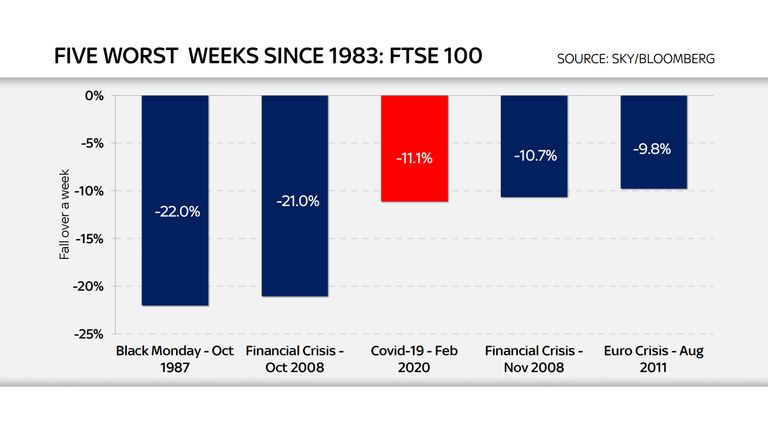

What is different about the sell-off this week has been the ferocity with which markets have fallen. The extent of the decline has shocked even experienced traders and investors.

The point is well made by a chart sent to clients today by Torsten Slok, the chief international economist at Deutsche Bank Securities.

It shows that the market correction over the past six trading sessions, of 12.03%, is the fastest fall of 10% or more in the S&P500, America's most important stock market index, ever seen. It puts other notorious falls in the market, such as the Asian crisis of October 1997, Black Monday in October 1987 and the bursting of the dot-com bubble, in April 2000, in the shade.

The US has been where the biggest drops in financial terms have been most eye-popping. With some $5trillion estimated to have been wiped from the value of global stock markets this week, some $221billion had been taken from Microsoft's stock market value in the week before today's opening on Wall Street and $219billion from Apple, while Alphabet/Google and Amazon respectively saw $144billion and $142billion knocked from their market worth.

Reverses in stock indices elsewhere around the world have been equally violent.

In Japan, home to the world's second biggest stock market after that of the US, the benchmark Nikkei 225 has fallen by 10% on the week - and that was even after being closed on Monday for a public holiday.

By contrast, the Hang Seng in Hong Kong has fallen by a comparatively mild 4.3% this week, although this arguably reflects the fact that it has been falling for longer after China became the first country to succumb to coronavirus.

However, it is down by 10% in the period going back to 17 January, when investors first started to worry about the impact of coronavirus in the Greater China region.

In Europe, things have been bloody, to say the least.

The FTSE-100 has finished the week 11% lower, the DAX 30 in Germany down by 12%, the CAC-40 in France down 12% and the MIB in Milan down by 11%. Among other major European markets, the SMI in Switzerland has fallen by 12%, the AEX in the Netherlands has fallen by 13% and the IBEX in Spain by 12%.

Within those indices, some of the falls have been more violent still, particularly in the travel and tourism sector.

For example, in the FTSE-100 this week, tour operator TUI has seen its shares fall by 30% and the low-cost airline EasyJet has seen its share price fall by 27%. International Airlines Group, the owner of British Airways and Aer Lingus, has fallen by 25% and the cruise line operator Carnival by 20%.

It has been a similar picture elsewhere: German airline Lufthansa has fallen by 22% this week and the Franco-Dutch carrier Air France KLM by 24%.

There are a plethora of interesting one-off records and milestones that have been notched up this week.

The oil price, for example, has suffered its worst weekly fall since the financial crisis of 2008 - with a barrel of Brent Crude falling by 14% and WTI, the main US crude benchmark, down by nearly 18% on concerns over a collapse in demand.

Perhaps the most striking indicator, outside the equity market, has been in the bond market and highlights the extent to which investors have dashed for safe havens.

The yield (which falls as the price rises) on 10-year US Treasuries, US government IOUs, has fallen to an all-time low. The yield goes down when the price rises.

US Treasuries are regarded as an exceptionally safe investment, Uncle Sam being regarded as among the most credit-worthy entities on the planet, but it is still quite something that people are prepared to lend to him for at a rate of just 1.155% - the yield hit today - for a period of 10 years.

In the Eurozone, where negative interest rates have for a while meant that sovereign debt trades with a negative yield in many cases - in other words, where investors are paying for the right to lend to a particular government - there have also been some dramatic moves.

The yield on 10-year Bunds, German government bonds, has fallen to -0.606%, its lowest since October last year, while the yield on 10-year French government debt fell to -0.316%, again, a level last seen in October last year.

The violence of the sell-off in equities can be explained by the circumstances. In 2008, during the financial crisis, markets could react in real time to developments.

There was also a degree of visibility in, for example, the way the authorities - the US Federal Reserve, the Bank of England and the European Central Bank - responded to events.

The problem this time around is that investors have no visibility as to how the COVID-19 outbreak will play out.

It is impossible to say how many cases will emerge, how many victims the virus will claim or the extent to which it may take off in individual countries.

Accordingly, even though the Chinese authorities appear to have done a reasonably good job in containing the virus, the extent to which the outbreak will ultimately hit global GDP is hard to predict.

Some have had an attempt, though, with Bank of America Securities today cutting its forecast for global GDPO growth this year from 3.1% to just 2.8%.

That is bound to have a knock-on effect on company earnings: Goldman Sachs dramatically said on Thursday that it expected to see no growth in US company earnings this year.

All this has led investors to speculate whether the world's central banks, notably the US Federal Reserve, will respond with interest rate cuts.

Investors had, until this week, taken comfort from the thought that the coronavirus outbreak in China might led to a temporary hit to supplies and, by extension, to growth - but that there would be a bounce-back in activity later in the year.

The concern now is that this could be something that goes on much longer and could hit employment.

There is scepticism that, under this scenario, even an interest rate cut would do much good. An interest rate cut will not, for example, necessarily get people to go to the shops, or buy a car, or attend concerts, conferences or festivals, or to get onto an aeroplane.

Larry Kudlow, director of the National Economic Council that advises Donald Trump, was doing his best to play down talk of a rate cut this evening.

He said: "Everyone should not over-react. In America we have an incredibly strong public health system and the president is taking rapid-fire actions to prevent further deterioration.

"We're dealing with this one day at a time."

Mr Kudlow said he was still watching events in China closely and had been reassured that, for example, Starbucks had begun reopening its outlets in China and that the Chinese factories that make Apple's iPhones had re-opened.

He added: "We're not going to take any precipitate actions. The markets have had a short term correction but we've been through this many, many times before.

"While nobody likes to see this as a front page story, or to see their asset prices go down, I don't think at this moment in time that this will have a long time impact."

He said he remembered how, when the stock market crashed in 1987, President Reagan had insisted that the US economy was "fundamentally sound" and that the economy had gone on to grow by between 3-4% in subsequent years.

And some market professionals are even starting to suggest shares have been over-sold.

Barry Bannister, head of institutional equity strategy at the stockbroker Stifel, told CNBC: "We've got a VIX of 49, the so-called 'fear index', is at 49 - it was 44 in March 2009, when the world really was coming to an end in an economic sense.

"So this seems to be a panic, an over-reaction, ready for a short-term bounce."