Drug wars, IS battles and child slaves: Hotspots gets behind the news

Friday 16 February 2018 09:28, UK

Sky News Specialist Correspondents

The fightback begins now. It's time to tackle the whole "fake news" phenomenon head on. And we've set out to do just that through Hotspots.

A warts and all portrayal of what is happening on the ground in some of the most inhospitable places on earth.

Our correspondents take you beyond the headlines to glimpse inside the unglamorous world of eyewitness reporting -starting off in a country where violent crime has become the norm.

Read more of Alex Crawford's explanation of Hotspots here.

On the frontline of Mexico's drug war with Stuart Ramsay

Mexico's official murder rate last year was nearly 30,000 people. The worst year since the government started counting bodies 20 years ago.

It is widely assumed that this is almost entirely caused by the drug wars raging between the country's Narco Cartels and the government.

The truth is violent crime, perhaps inspired by the brutality of the cartel gangs, has become the norm.

"It was like being on the set of the Godfather - the whole trip", Stuart Ramsay, Chief Correspondent

Murdering business or political opponents is taking over from legal action and the ballot box.

We travelled to one of the worst hit areas in Mexico, the formerly glamorous playground of the wealthy, Acapulco, to see what is happening to society and why it has become so violent.

We wanted to see why the government has so spectacularly failed to control the gangs or guarantee normal peaceful lives for its citizens.

This was a difficult trip in many ways. It has taken six months to meet the people who grow opium and heroin producing poppies high in the mountains and to meet the farmers and crime bosses who control the business.

We are the first outsiders they have ever allowed in.

With the police on patrol we came across the murder scenes of 19 people in the first 24 hours of our arrival.

Many more people died that day but we saw 19. Meeting the families still struggling to control their grief was difficult and will stay with us all forever.

This was raw emotion and difficult.

We had lunch with a man who could have us killed in an instant and was effectively interviewing us before he gave permission to film. It was like being on the set of the Godfather - the whole trip.

I have covered the drug wars in Mexico for years now. Meeting both the legal side and the crime side during multiple trips. But it is worse now.

All society is being infected by a virus of violent crime, corruption and collusion is endemic and there appears absolutely no way to stop it.

Even a hitman acquaintance is appalled at the brutality he is asked to mete out on targets. When at hitman is appalled - somebody should be listening. But nobody is.

In the battle against IS with Katie Stallard-Blanchette

As the Islamic State lost ground in Iraq and Syria last year, its followers tried to open a new front in Marawi, in the southern Philippines.

Militants from two local groups, under the leadership of the IS "emir" for south-east Asia, Isnilon Hapilon, seized control of the commercial centre of the majority Muslim city, along with hundreds of hostages, and fought government forces for five months, in the country's longest urban conflict since WWII.

The southern island of Mindanao has a long history of separatist violence, poverty and allegiance to local clan groups above the national government. The island has the highest concentration of Muslims in this predominantly catholic nation.

"Liberation looked like devastation", Katie Stallard, Asia Correspondent

This conflict was seen as a test of whether an IS-linked group could take and hold territory outside the Middle East.

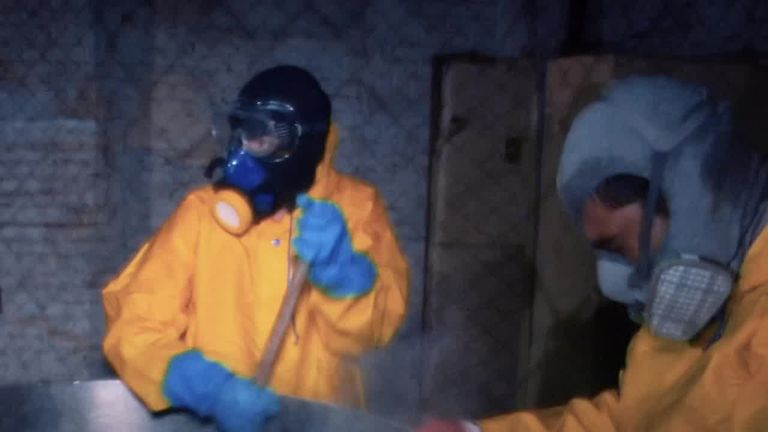

The fighting was intense and there was a constant risk from stray bullets, so our team had to wear full protective gear (ballistic helmets and flak jackets) whenever we entered the city.

An Australian reporter had been hit in the neck shortly before our first deployment (thankfully he recovered fully), so we were all very aware of the danger.

There were a number of close calls, but the most serious was when we came under targeted, direct fire as we tried to enter a building to speak to some of the civilians trapped by the fighting, with a round landing around a metre from our team.

As we took cover inside, a fire started in or near the building, it wasn't clear which, and there were no other exits, so we had no choice but to run back out the direction we had just been shot at.

It was pretty nerve-racking running back out into the road, and everyone was pretty shaken, particularly watching the footage back to see how close the shot had been.

The challenge now for the government will be rebuilding the city, large parts of which have been levelled by air strikes, and with it the trust of the hundreds of thousands of people who have lost their homes, and in many cases are returning home to find their belongings looted.

With slave child miners in Africa with Alex Crawford

This is a story about modern-day child slaves - and the shocking reality is, you're probably unwittingly using a device powered with a mineral extracted by their tiny hands.

There are thousands of unregulated, unmonitored mines operating in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). And they are crawling with an army of children working by hand in dangerous conditions for a pittance.

We saw children as young as four involved in the work.

A 12-hour-long day of punishing manual labour may earn the children the equivalent of a few British pence, if they're lucky.

Many people reading this may not be able to pinpoint where the DRC is in Africa but the chances are you're the beneficiary of the children's backbreaking work there.

The soil beneath DRC is rich in minerals - particularly cobalt which is fast becoming more precious than gold. More than half the world's cobalt comes from DRC.

It's an essential component of lithium-ion batteries used in smartphones, electric cars and computers which make billions for multi-national corporations.

But the child workers - and even the adults in the DRC - barely see any of the wealth and the central African country is one of the poorest in the world.

We visited a string of mines in the Katanga Province of DRC, talking to dozens of people and there were children working at all of them.

"The father had to make a decision to let go of the only thing in his life that was keeping him going", Alex Crawford, Sky News Special Correspondent

Dorsen and Richard stood out as they were the tiniest boys working there and the rain made them look even more vulnerable. We made them the central figures in our report.

After our film was shown on TV, we were inundated with offers to help them and one locally-run but internationally-funded charity paid for their education.

It meant taking the boys away from their families so they could learn in safety and that was one of many heart-breaking moments in a story packed full of them.

:: Watch Hotspots on Thursday night at 10pm on Sky Atlantic, and Friday night on Sky News.