General election: Why the economic battleground has shifted to the left

Liberal Democrat deputy leader Sir Ed Davey says "the Conservative Party is no longer the Conservative Party".

Friday 29 November 2019 09:38, UK

Talk to a political theorist long enough and there is a chance they might start talking about the "Overton Window".

Like most academic jargon, it is one of those terms designed to alienate outsiders and make insiders feel smug.

But underlying it is actually a rather simple idea: that over time a society's preferences for certain types of policies tend to shift.

The idea, put forward in the 1990s by Joseph Overton, an obscure American think tank executive from Michigan, is that it is possible to gradually shift a country's economic and social appetites along a spectrum.

When he was leader of the Labour Party, Ed Miliband and his staff liked to talk about how they expected the centre ground to shift left.

"The Overton Window will shift in our direction," they would say.

Ed Miliband is no longer Labour leader but today it is worth asking whether he might just have been right.

For it is hard to escape the notion that this election is being fought on an economic battleground that has shifted markedly to the left.

Given their manifestos imply an enormous difference in fiscal terms between the Labour and Conservative parties, that might seem a preposterous idea.

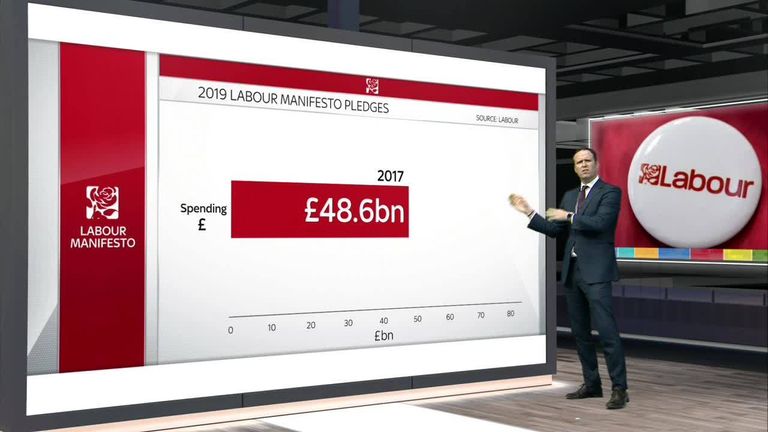

Doesn't the fact that the Labour Party are proposing to spend an extra £28 for every pound the Tories are imply the gap between the two major parties has never been so wide?

In a sense, yes.

But consider the nature of the Conservative platform.

They are in favour of more government spending - albeit not half (or indeed a fraction) as much as the Labour Party.

They are in favour of intervention in energy markets and, for that matter, financial markets (where they want to push mortgage companies to offer lifetime fixed rate mortgages).

They want to impose extra barriers on trade - that, after all, is the inevitable consequence of leaving the single market and customs union.

And they want to raise the minimum wage beyond where Ed Miliband wanted it a few years ago (and this is coming from a party which voted against the minimum wage in the 1990s).

True, the pledges may be nowhere near as radical as what Labour is proposing.

Yet it is hard to think of another Tory manifesto which has been as left wing as the one on offer this time around.

Perhaps that's simply a consequence of a decade of austerity.

Perhaps it signifies a genuine shift in the Overton Window.

Either way, it is remarkable how far the Conservative Party has moved, even since David Cameron's time.

With an activist industrial strategy, energy price caps and a pledge to increase public spending to the highest level since the 1970s, it is, in some senses, more left-wing in policy terms than the Labour party of the Blair or indeed Miliband era.

According to Sajid Javid, those shifts to policies like a higher minimum wage are simply based on empirical findings.

"You should be led by the evidence," he says.

"Look at the recent change in the national living wage. I've announced that that we're going to get it to £10.50, and we're going to reduce the ages eligible from 21 and above.

"It's the Conservatives doing that. It will help end low pay forever in this country."

Yet he insists that does not change the defining identity of his party.

"Based on evidence, there are new things that we're doing to support the British people, but at the same time our basic approach - that is sound public finances, supporting free enterprise, supporting entrepreneurs - none of that has changed, and you contrast that today with Labour, it's black and white."

Yet in some senses even Labour's John McDonnell believes that shift is happening.

"It's a victory in the sense we're hegemonising the debate. We've won the argument to a large extent, so they've had to come on to that debate, but not delivering in any effect."

For Sir Ed Davey of the Liberal Democrats, this convergence presents an opportunity.

He says: "What is notable about this election is all parties are talking about spending more and that's probably left the electorate quite confused.

"The Conservatives under Boris Johnson are chasing Labour votes.

"And that has shifted their position. I mean, the Conservative Party is no longer the Conservative Party if you want my honest opinion.

"Basically you've got a choice of a party that believes in free trade, that believes in markets, in the Liberal Democrats.

"You've got the Conservative Party, who wants to put up trade barriers wants to pull us out of markets.

"And you've got the Labour Party, who've gone to the left, who believe the state should run everything.

"That is a unique political backdrop to the economic debate."

Yet it's worth pointing out that actually the Liberal Democrats are planning to borrow and spend even more than the Conservative Party.

Actually, all the major parties have shifted their fiscal plans considerably to the left.

In part, this is a consequence of the weariness around the country with austerity.

In part it is because the government deficit is finally now back to what you might call normal levels - or at least the kinds of levels that were familiar from before the financial crisis.

In part it is because the Conservative government has already had to abandon its existing fiscal rules - the guidelines on how much it plans to borrow - and the reaction from markets was, well, non-existent.

In other words, there seems to be something of an open door for the next government to borrow to invest more.

Look at the investment plans of the major parties and there is far less difference than ever before.

Last election it was only the Labour and Liberal Democrat parties pledging to splurge more on investment.

This time around, the Tories have joined them, promising to borrow and invest a whopping £100bn over the next half a decade.

This would amount to the biggest spending spree in almost two decades.

And certainly the biggest increase from any modern Conservative government.

Amid this focus on borrowing more and spending more the relationship between politicians and business seems to be at a low ebb.

Brexit is part of the explanation, but a deeper issue business people talk about is that the usual kind of dialogue they tended to enjoy with government and the opposition is far less free and easy than it once was.

Business is no longer regarded as part of the solution.

Perhaps that's no surprise given the prime minister is the man who once said "**** business".

Yet all the normal rules and the normal gravitational pulls one tends to experience during elections seem to have dissolved away this time.

:: Listen to All Out Politics on , , ,

That makes any predictions about the result all the more difficult.

The issue isn't merely the straightforward psephological problem: that you have two parties - the Lib Dems and Brexit Party - taking votes from both the big two.

It is that no one is quite sure how far the Overton Window has shifted.

Both the major parties clearly suspect it's moved.

They suspect the British people want more spending and more left-wing policies.

But they have no idea how much.

So in this election there is actually less choice than in previous polls.

All the parties want to send Britain further to the left.

The main decision - as embodied in the party manifestos - is over the speed of that transition.

The Brexit Election on Sky News - the fastest results and in-depth analysis on mobile, TV and radio.

- Watch Dermot Murnaghan live from 9pm on 12 December

- See the exit poll at 10pm

- Watch KayBurley@Breakfast election special on 13 December

- Find out what happens next in All Out Politics special from 9am with Adam Boulton