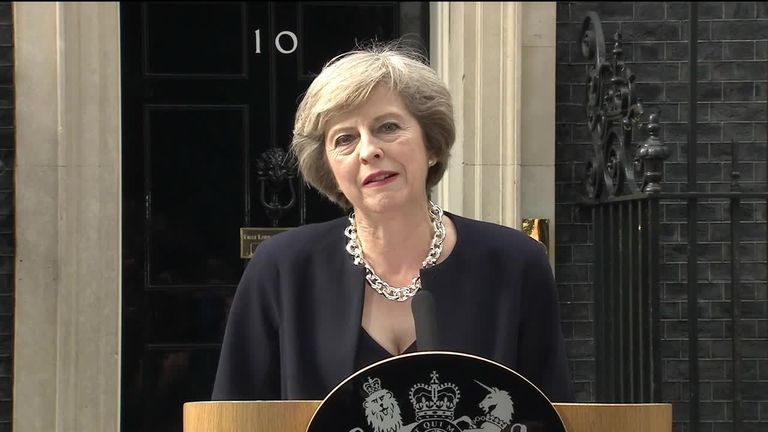

Theresa May bemoans the rise of populism, but she should look in the mirror

So often it felt as if the person who most needed to watch her speech was the prime minister herself, writes Lewis Goodall.

Saturday 20 July 2019 09:30, UK

Theresa May has given her last major speech as prime minister. Her theme? A lamentation over the development and growth of populism in Britain, a peroration on the virtues of compromise, a repudiation of the politics of "simplistic solutions" and of "us and them".

It was a decent speech, with some interesting thoughts. But given these were the themes, Mrs May seemed the least likely person to deliver it.

So often it felt as if the person who most needed to watch this speech was Mrs May, about six months ago.

For her to hail the value of compromise was darkly funny.

This is the prime minister who attempted to ram the same deal through parliament, unchanged, grinding it through sheer attrition, no fewer than three times.

She refused to budge an inch; insisting parliament bent to her will. They refused and so her premiership ended.

But it didn't need to be that way - it is possible had she bent, just a bit, she might not be on the verge of leaving office now.

Mrs May went on to quote Eisenhower. This was telling. It was clear from the tone of her speech that she was playing for history, pitching herself as akin to Ike, the great general, a national unifier.

That is pure revisionism. It is possible, that by comparison to what is to come, her time in office might not be seen as divisive as it actually was.

:: Listen to All Out Politics on , , ,

But the truth is there have been few politicians as schismatic, as fuelling of the politics of us and them, as populist, as Mrs May.

It seems peculiar to think that of her: the quiet, reserved technocrat, the Thames Valley Tory, the vicar's daughter.

She seems so often to exude a dutiful Englishness, one antithetical to the fervid strong men populists that so characterise our age. Yet look not at her aura but her words:

"Just listen to the way a lot of politicians and commentators talk about the public.

"They find your patriotism distasteful, your concerns about immigration parochial, your views about crime illiberal, your attachment to your job security inconvenient… But today, too many people in positions of power behave as though they have more in common with international elites than with the people down the road, the people they employ, the people they pass in the street.

"But if you believe you're a citizen of the world, you're a citizen of nowhere. You don't understand what the very word 'citizenship' means."

Not the words of a Donald Trump, a Boris Johnson, a Matteo Salvini or Marine le Pen, but the vicar's daughter, Mrs May.

When historians write the history of the May premiership, they will doubtless focus on the obvious mistakes, but they will also marvel at the tone she struck: from the off, a Remainer playing a Leaver, desperate to prove her Brexiter spurs, she focused relentlessly on the 17.4 million.

It was from them she derived her legitimacy and mandate, never more so than when she lost any legitimacy or mandate of her own after the botched election.

She made no attempt to bring the country together, to seek the sort of compromise she so lauded today.

Her rhetoric likewise became anchored in the most estranging language; in the idea that the right of the narrow majority trumped all of the large minority; in a language of nowhere vs somewhere, real people vs unreal people, of their "will" and elites determined to thwart it.

She spoke of a "quiet revolution" by "the people" to "defy the establishment".

Never was this truer than in the endgame of her premiership, as she repeatedly took to the airwaves to decry MPs and parliament itself for doing its job.

I have noticed and reported on a shift among the public this year.

Where once they despaired at the occupants of the political system, now they rally against the system itself, one they now consider otiose and antithetical to their interests.

Mrs May did more than most to fuel that impression. People believe that Westminster elites and parliament are seeking to betray the public.

Why? Because their prime minister told them so.

Just because she did it with less fanfare and less bravura and bluster than Nigel Farage, didn't make it less corrosive.

On the contrary, it was probably more influential because it was said not by the familiar rabble rouser, on a stage in Bolton, Union Jack in his lapel and pint in hand, but from the quiet, reserved prime minister of the United Kingdom on the floor of the House of Commons.

It is no surprise, then, that when a group of academics ranked leading politicians speeches on an index of populism, earlier this year, Mrs May had the same score as Brazilian arch populist Jair Bolsinaro and wasn't even a million miles away from Mr Trump himself.

Hers was a style where and again she found enemies within the British political system, each time pitting herself as "the people's" representative against the entrenched established interests: the courts, the media, parliament itself, the European Union.

How many speeches we endured in Downing Street or elsewhere, with Mrs May playing the same tune, each time with a newly acquired enemy.

I offer no view as to whether she was right or wrong, whether these interests were indeed seeking to override the public will; but there can be no doubt that, justified or not, it is a sea of politics in which Mr Trump and his adherents swim.

And so she often seemed, not the ultimate custodian of our political institutions that she ought as prime minister to have been, but instead their assailant.

The May politics of yesteryear contributed so much to the fevered politics of now and will be the bedrock of all of the frantic tomorrows to come.

So Mrs May, if you want someone to blame for the rise of populism in Britain, to the divisiveness which now so corrodes us, you need look no further, in the long years ahead and the new free time you have, than the mirror.